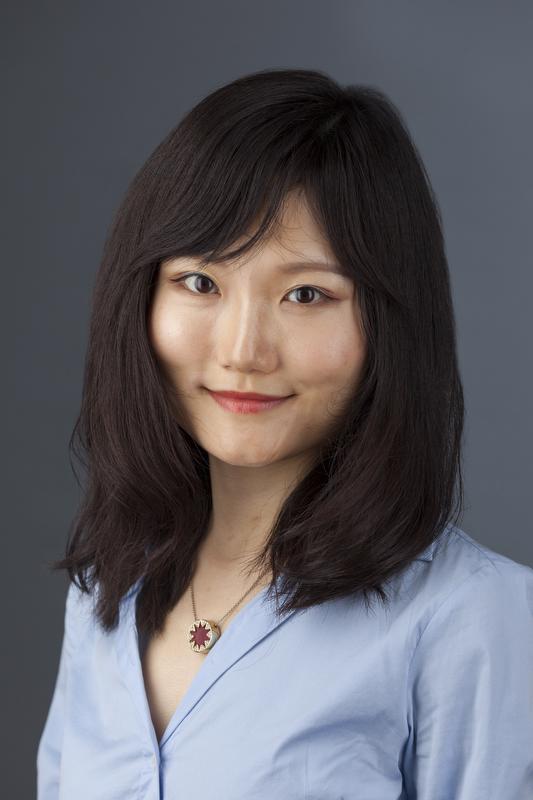

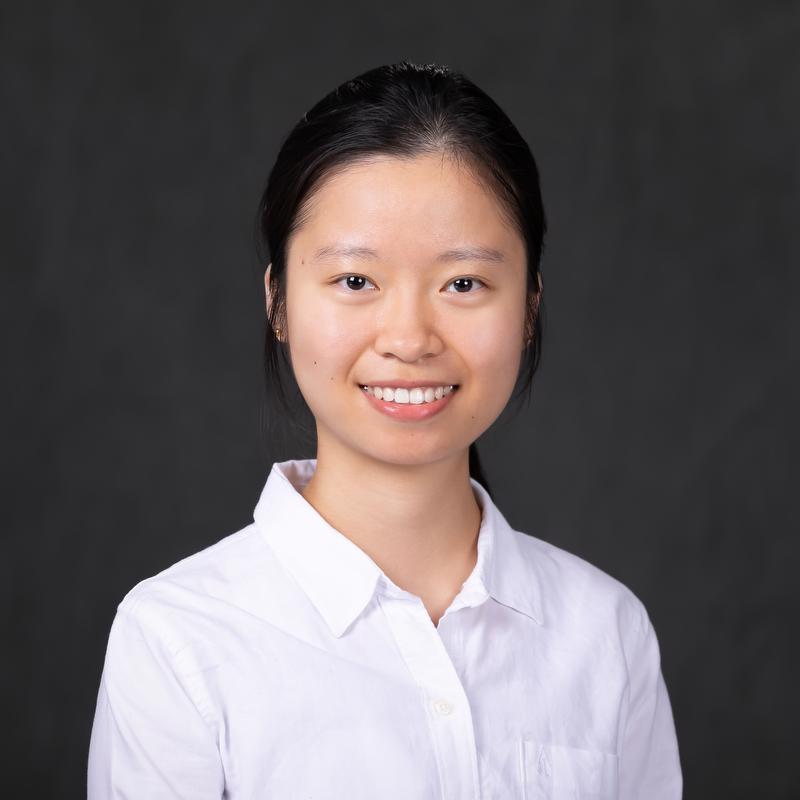

Catching Up with Jenny Robinson, former Pilot Awardee (2020-2021)

By Kelly Hale , Marketing & Communications Specialist

May 25, 2023

Currently: University of Washington, Assistant Professor – Mechanical Engineering; Endowed Chair in Women’s Sports Medicine and Lifetime Fitness – Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine

For Jenny Robinson, playing competitive soccer was not only a goal but a reality until she first injured her knee at the age of 12, while planning to attend the Olympic development program tryouts that year. And as she returned from the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and meniscus tear, osteoarthritis developed over time.

“I was in a lot of pain at 15, 16 years old and the surgeon told me I had post traumatic osteoarthritis and I should really stop playing soccer,” she said, noting that at the time there weren’t many pediatric orthopedic surgeons. “But in my mind that wasn’t happening. Soccer was what I wanted to do and play in college (where she did end up playing club soccer).

“As I dealt with my injury, I was fascinated by the orthopedic surgery process and that there were options to repair my knee. However, I was also upset that these options were not ideal as they required using healthy tissue from elsewhere in my body and the process did not get my knee back to full function. I think that’s when I really decided that research could be an option for me. I already knew I liked science and engineering; I liked solving problems so this was the right path.”

And for someone who doesn’t like to be bored, Robinson has led an exciting path to where she is now.

“I did my undergraduate work at Rice University and got my first experience working in a tissue engineering lab; I just cold emailed professors and am grateful that Dr. Tony Mikos, a pioneer in tissue engineering, said he had a position in his lab” she said.

And from there, she earned her Ph.D. at Texas A&M, completed postdoctoral training at Columbia University, spent a summer in Ireland working in a lab and doing a fellowship in Singapore the year after undergrad.

“At Texas A&M, I worked in a biomaterials lab focused on tuning material properties by controlling polymer chemistry and fabrication parameters to mimic native tissue properties. This work was fascinating to me because you could tangibly observe and measure how altering one parameter could drastically change material properties.” she said. “We worked with different biomaterial fabrication techniques, like 3-D printing, in our lab.”

“I think my work at Columbia really helped spark my interest in the differences between sexes. I worked with a PhD-trained orthodontist and he was seeing more jaw pain in women and we started to study how estrogen impacted the tissue in a mouse model.”

When she joined the University of Kansas – Lawrence as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Chemical and Petroleum Engineering, she started doing more research on tissue and cell regeneration when it came to the differences in men and women, with a focus on the knee meniscus.

“For my Pilot research, I studied the sex differences in injury and regeneration and that work actually led me to the University of Washington,” she said. “I wanted to study why ACL tears and meniscal tears were happening more in female athletes, which isn’t as researched.”

It all started with looking at when tissue is removed due to injury and how that leads to osteoarthritis.

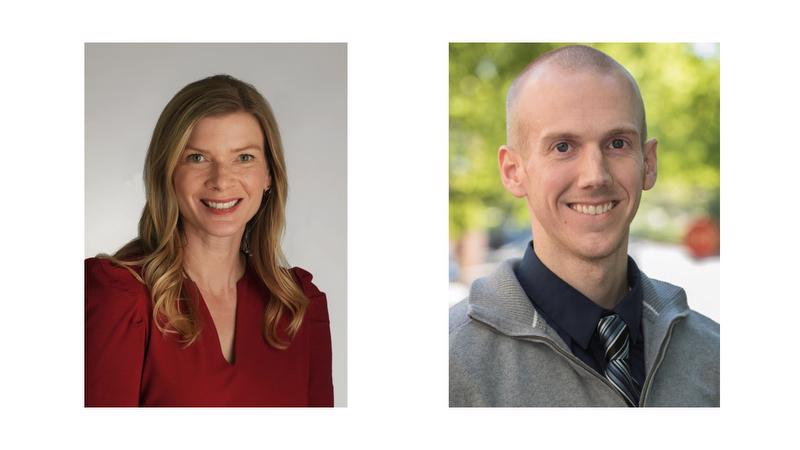

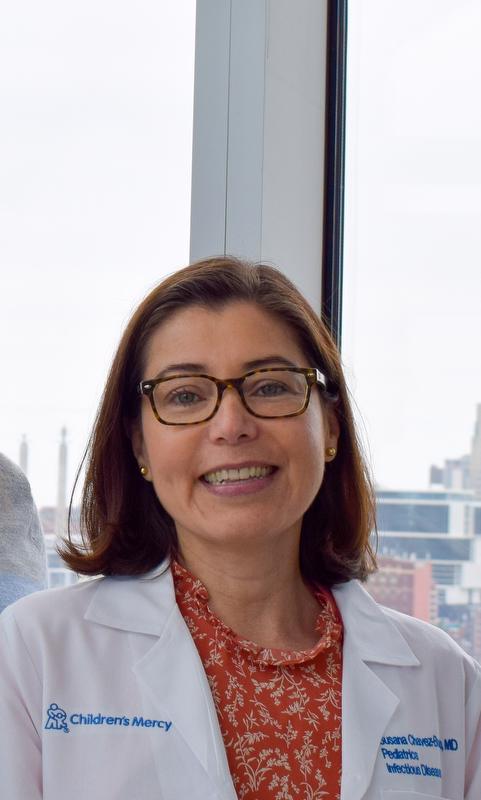

“We worked with Dr. Donna Pacicca, pediatric orthopedic surgeon, and Dr. Emily Farrow, Director of Lab Operations at the Genomic Medicine Center, both at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, to get meniscus tissue from both males and females and do bulk RNA sequencing to assess transcriptional signatures that may be different in injured tissues in females compared to males of similar ages. We had three participants from each sex and wanted to see how cells responded to estrogen,” she said. “And we’re still working on that. The more we study, the more we realize that there is so much more to learn.

“It’s been great because it’s a cross discipline collaboration for a complex problem and Frontiers really promoted that when I started my Pilot project.”

And one thing that has been learned from the research is that even though there were three males and three females who participated, there was still a great deal of donor variability.

“When there’s an injury, tissue is impacted and it signals to immune cells that they need to clean up the area and then send out signals to make new tissue to repair the injury,” she said. “But the process may be different in the sexes. We’re studying if it is hormone dependent. Once we have the impact, how do we use that data to change how athletes train, but also how they come back from an injury.”

“There’s a company out there, Orecco, working with high performance athletes and tracking their menstrual cycle and then providing suggestions for nutritional and training decisions. The research I’m working on could help us better prepare athletes in all phases and we could personalize training for them to help prevent injuries using the menstrual tracking method.”

And during her time in research, the one thing she has noticed is that women researchers are driving the research on sex differences and conditions predominantly impacting women.

“Women have definitely started joining this research area more over the last few years,” she said. “I know some women researchers who are studying tissue mechanics in pregnancy because no one else was. This just helps all of us.”

Currently her lab is working on projects related to the knee meniscus, where they are making fibers and hydrogels to mimic the healthy and injured tissue mechanics and then using them as microenvironment to understand how human meniscal cells from injured patients respond. They are also investigating how macrophages, cells of the innate immune system that are critical for tissue healing and regeneration, from male and female donors differentially respond to the engineered microenvironments.

The exciting path for Robinson continues.

Latest Articles

View All Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

KL2 Scholar · News

KL2 Scholar · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

KL2 Scholar · News

KL2 Scholar · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

News

News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

News

News

News

News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

Events

Events

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

News

News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

KL2 Scholar · News

KL2 Scholar · News

News

News

KL2 Scholar · News

KL2 Scholar · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

News

News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

Services · News

Services · News

News

News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

KL2 Scholar · News

KL2 Scholar · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

KL2 Scholar · News

KL2 Scholar · News

News

News

News

News

KL2 Scholar · News

KL2 Scholar · News

KL2 Scholar

KL2 Scholar

News

News

News

News

KL2 Scholar · News

KL2 Scholar · News

News

News

News · In the Community · Funded Projects

News · In the Community · Funded Projects

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

News

News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Events · News

Events · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

News · In the Community · Funded Projects

News · In the Community · Funded Projects

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

KL2 Scholar · News

KL2 Scholar · News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

News

News

News

News

KL2 Scholar · News

KL2 Scholar · News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

News

News

News

News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Events · News

Events · News

KL2 Scholar · News

KL2 Scholar · News

News

News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

News

News

Partner News · News

Partner News · News

News · In the Community

News · In the Community

0

0

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

News

News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

News

News

Events · News

Events · News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

News

News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

News

News

Partner News · News

Partner News · News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

Events · News

Events · News

KL2 Scholar · News

KL2 Scholar · News

News

News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

News · KL2 Scholar

News · KL2 Scholar

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

Events · News

Events · News

News

News

News

News

News

News

40

40

News

News

News

News

TL1 Trainee · News

TL1 Trainee · News

News

News

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

News · In the Community

News · In the Community

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

In the Community

In the Community

News · In the Community · Partner News

News · In the Community · Partner News

KL2 Scholar · News

KL2 Scholar · News

News · In the Community

News · In the Community

Events · News · Services

Events · News · Services

Funded Projects · News

Funded Projects · News

KL2 Scholar · Funded Projects · News

KL2 Scholar · Funded Projects · News

TL1 Trainee · Funded Projects · News

TL1 Trainee · Funded Projects · News

News

News

News

News

KL2 Scholar · Funded Projects

KL2 Scholar · Funded Projects

KL2 Scholar · Funded Projects

KL2 Scholar · Funded Projects

Events · News

Events · News

News

News

KL2 Scholar · Funded Projects

KL2 Scholar · Funded Projects

News

News

Funded Projects

Funded Projects

TL1 Trainee

TL1 Trainee

News

News

Funded Projects

Funded Projects